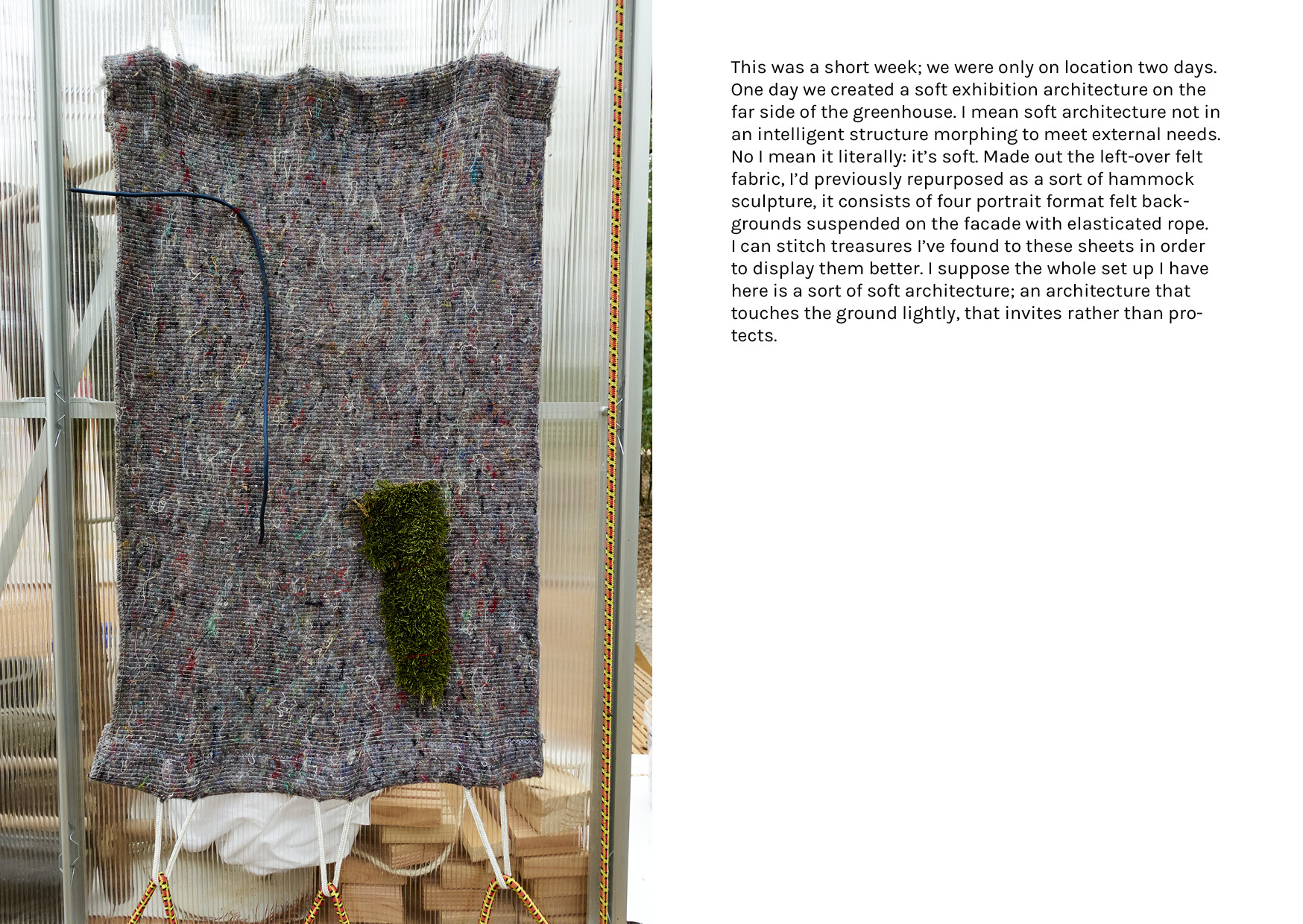

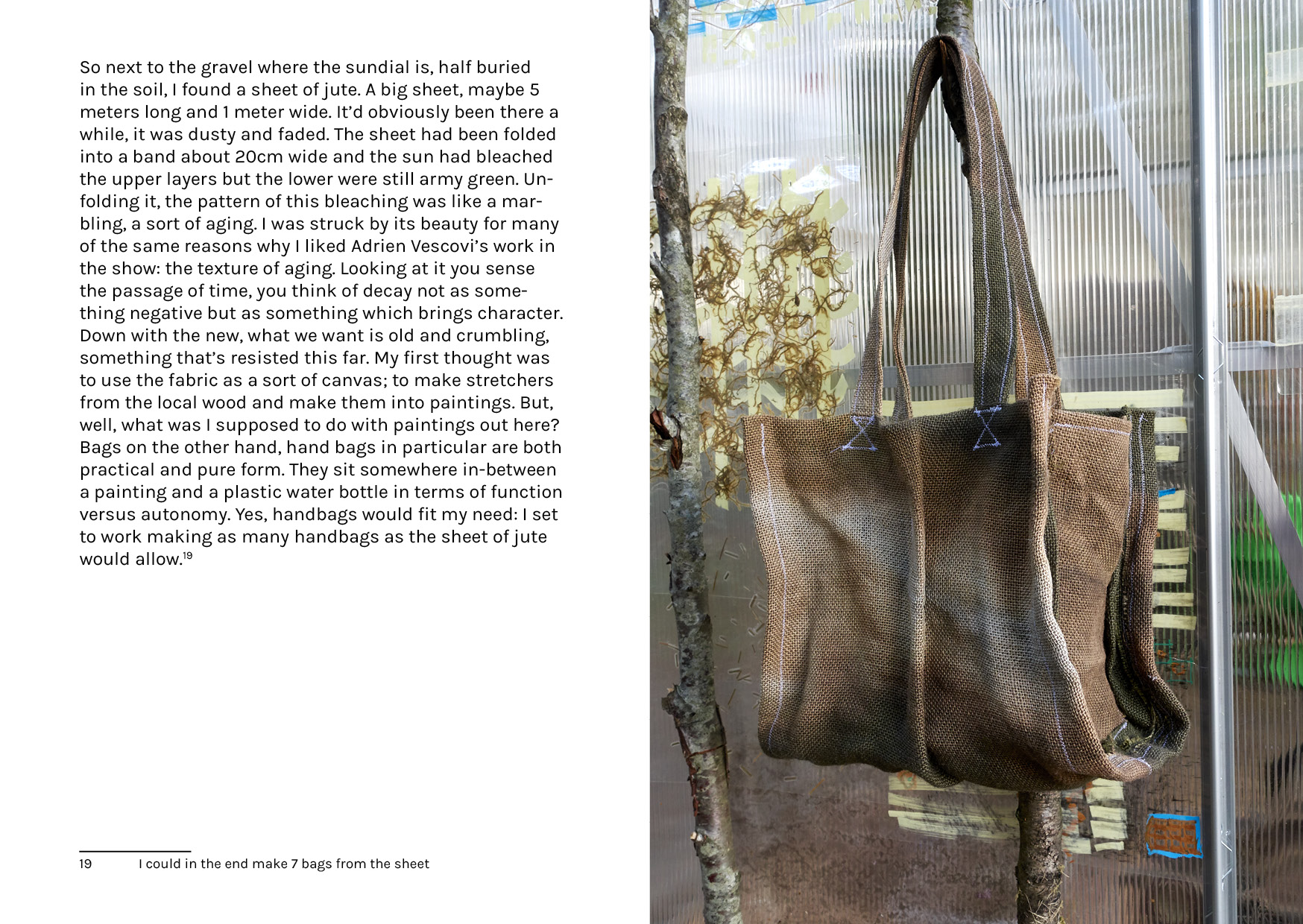

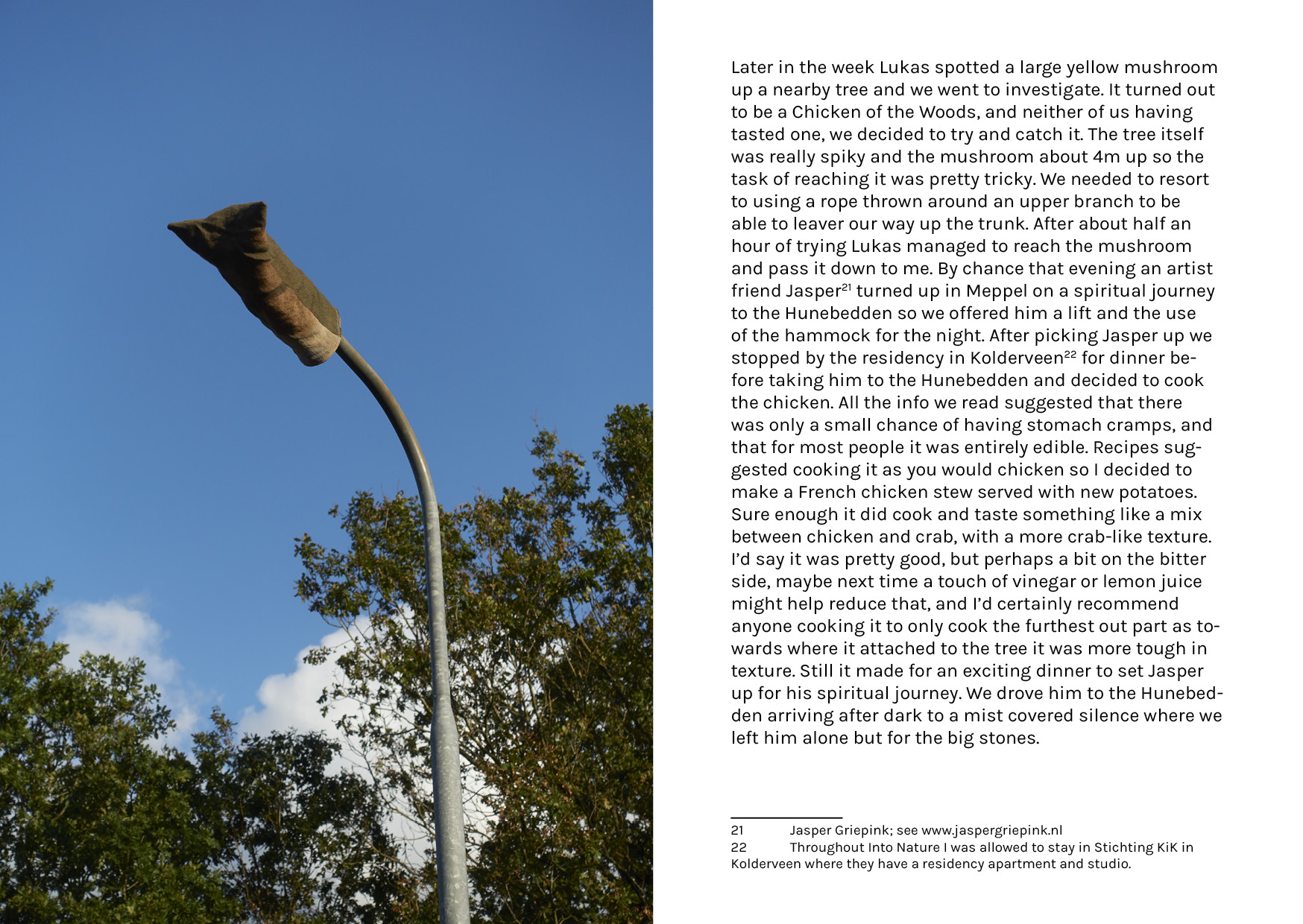

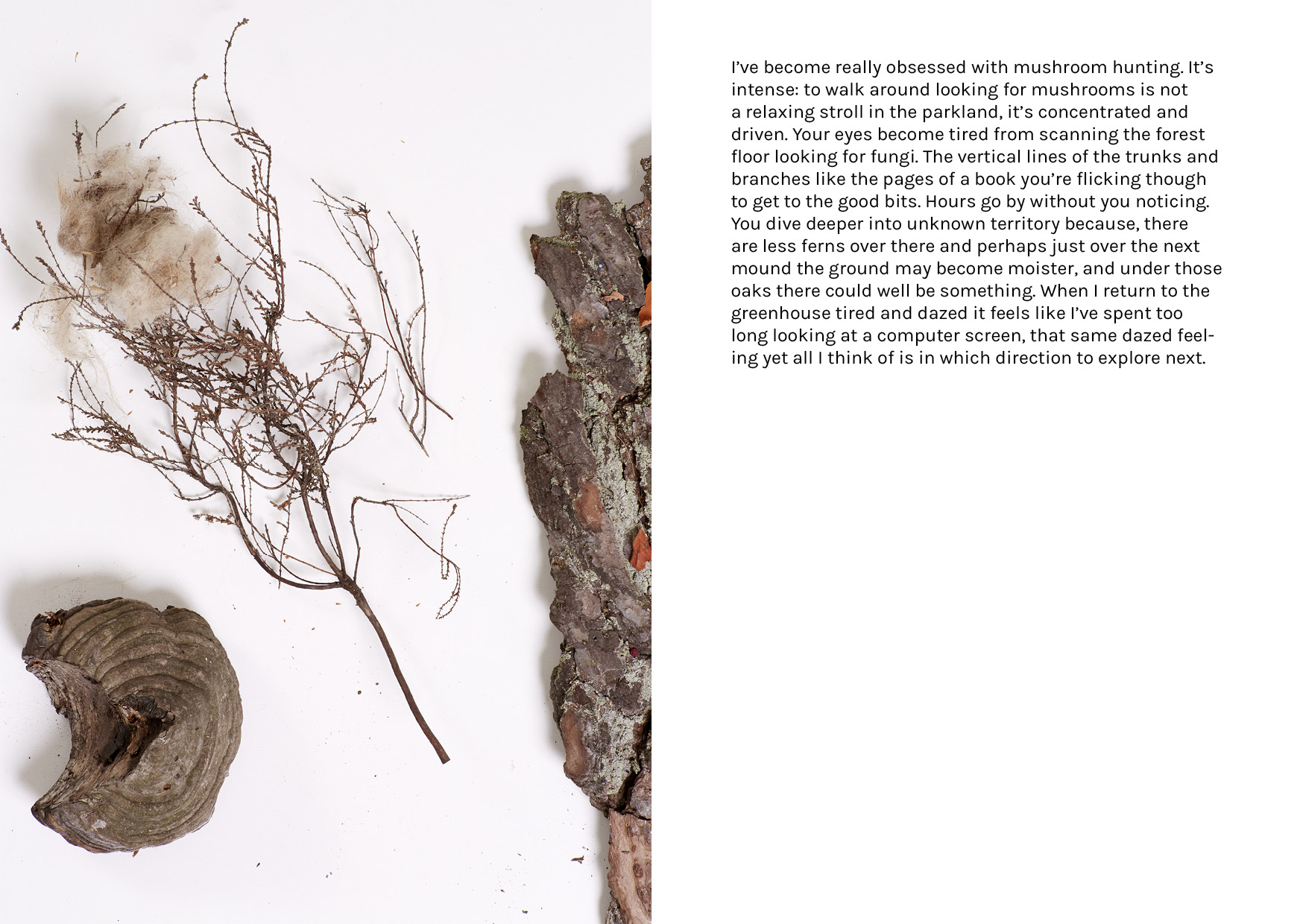

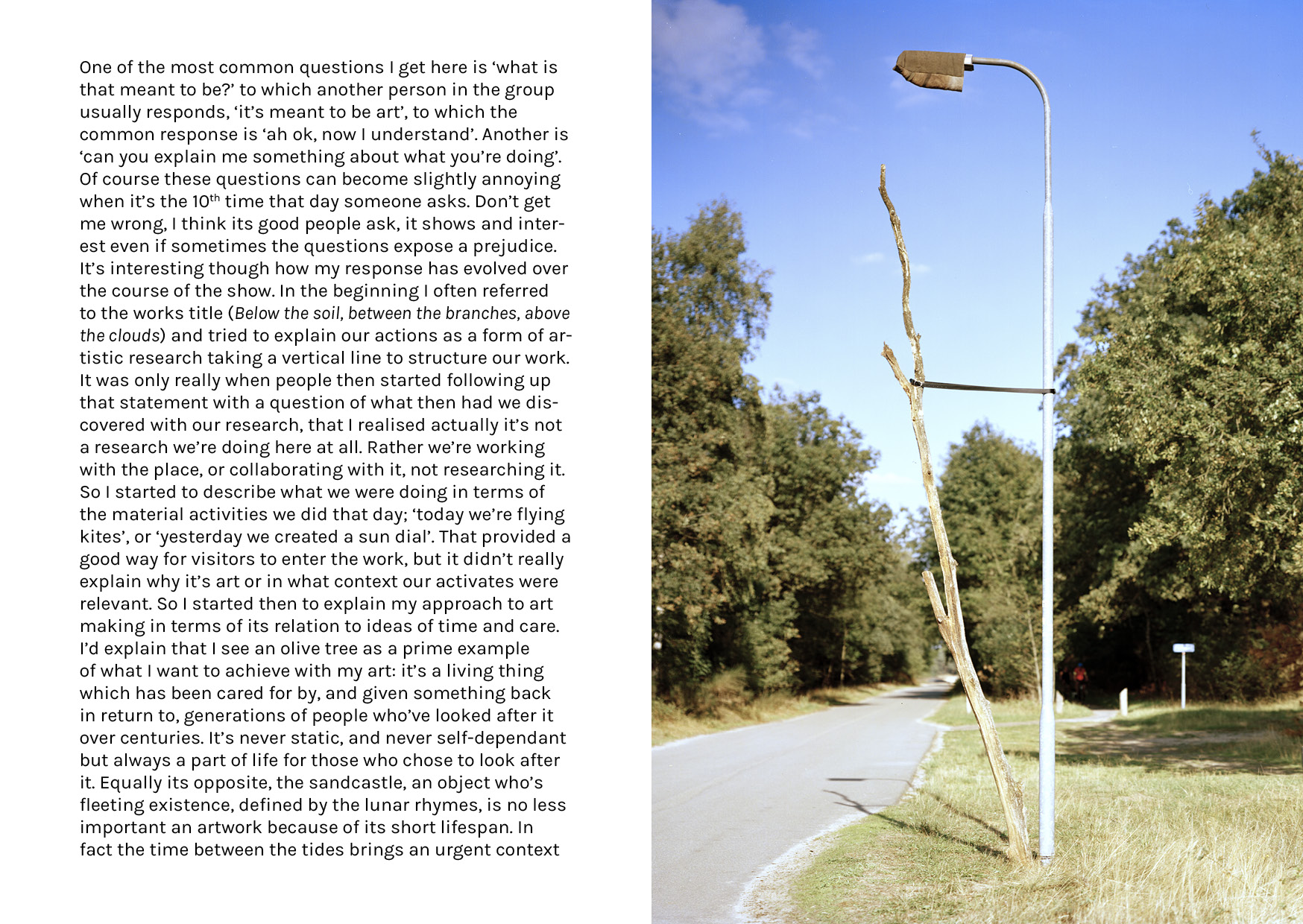

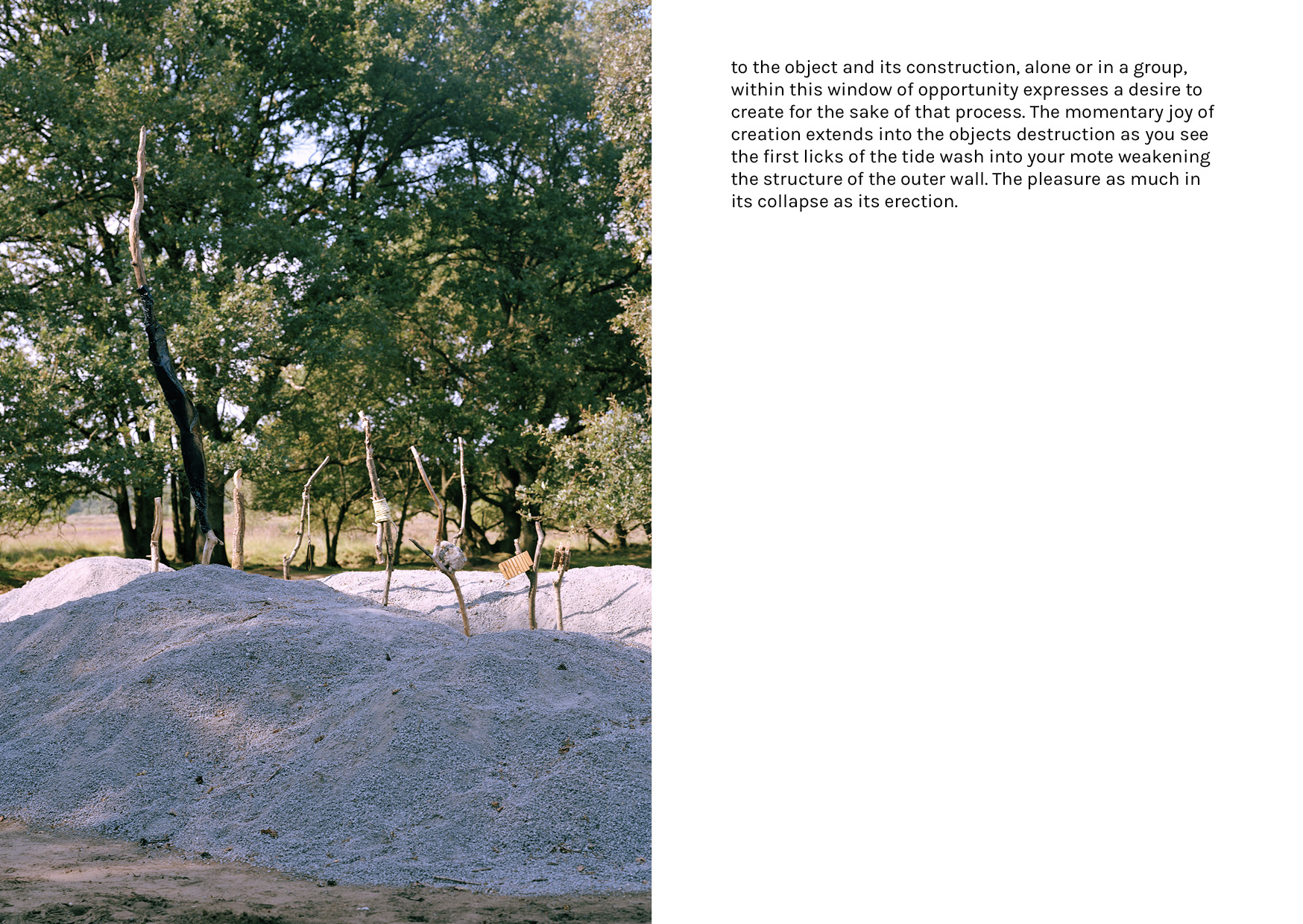

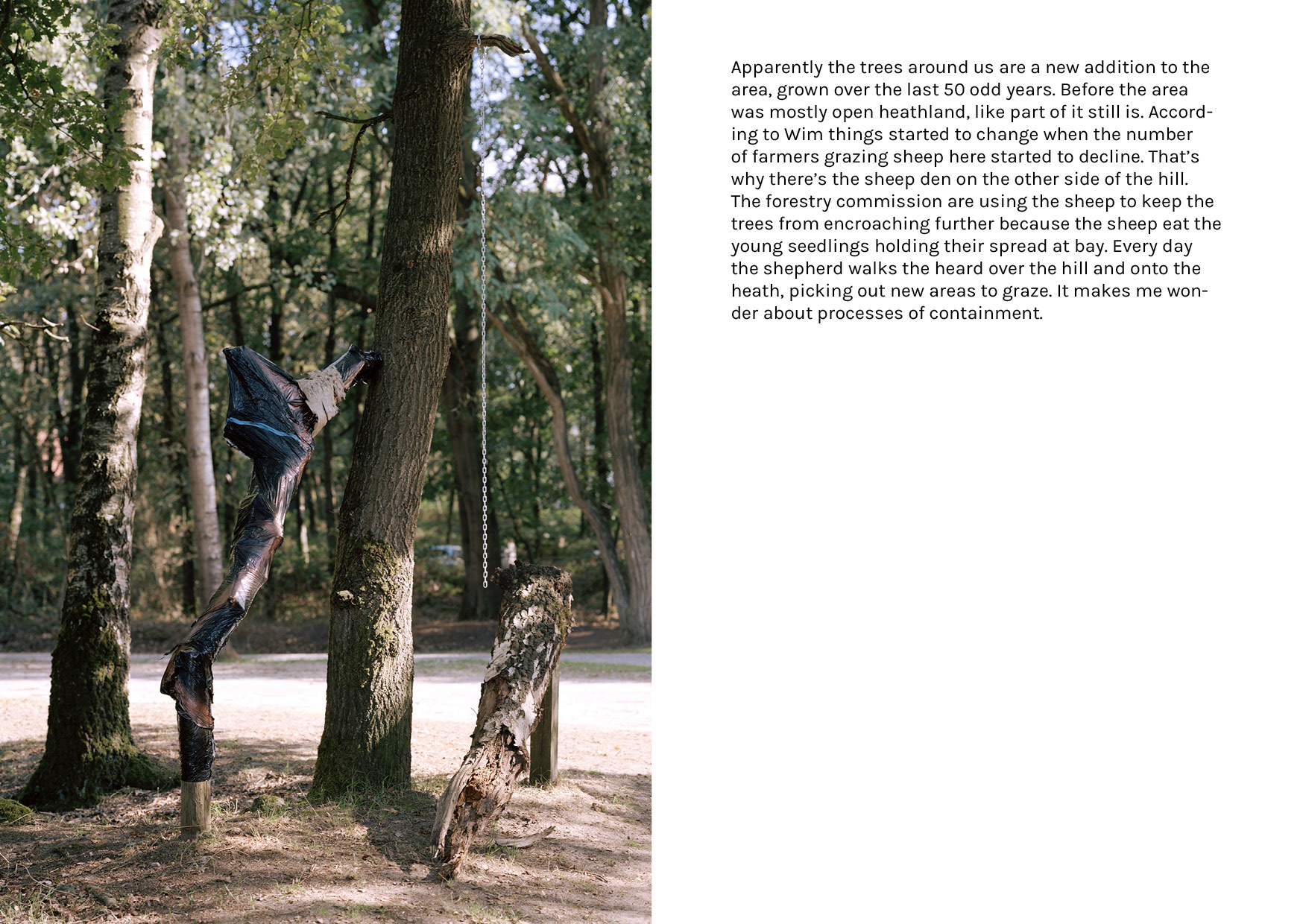

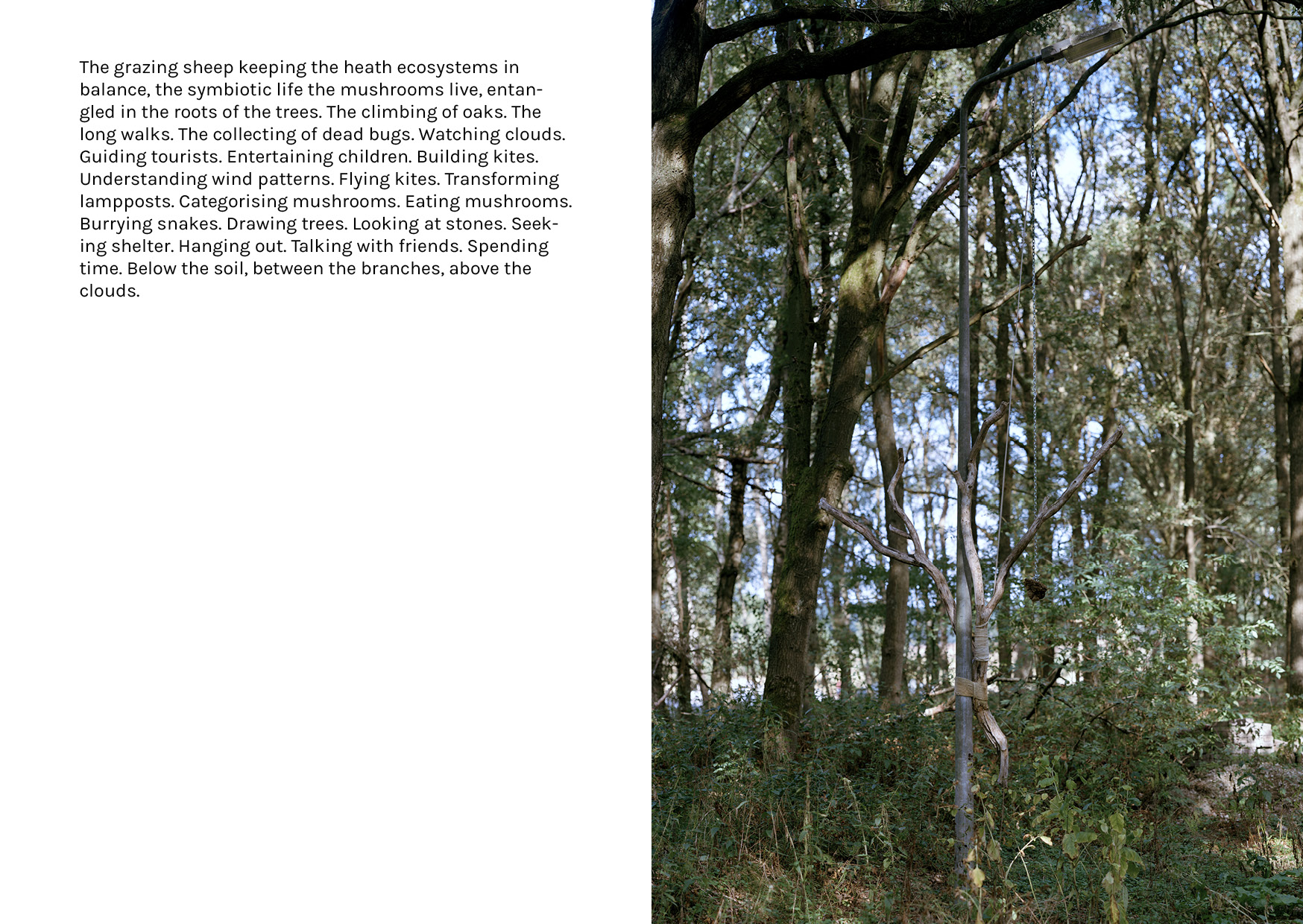

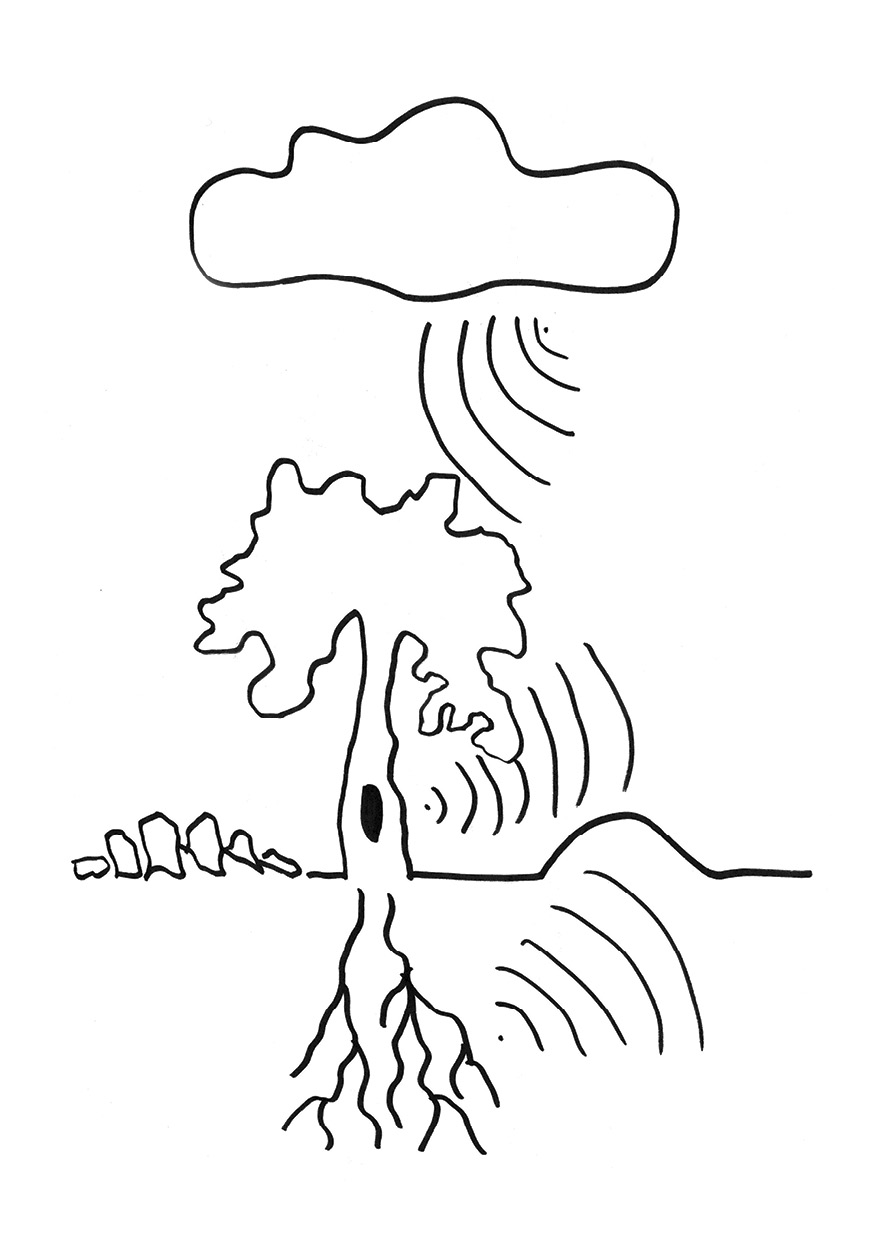

During Into Nature Thomson will create a mobile research camp located on the Holtingerveld. The research camp will focus on different forms of communication occurring on the heath: visible and invisible, verbal and non-verbal. He will structure this by taking a vertical division (below the soil, between the branches and above the clouds) as a way of organising his activates. Activates there will include amongst other things: the speculative mapping of underground plant communication, attempting to feel a connection with the afterlife by listening to the dolmen and burial mounds, the mapping of tree patterns and density, the climbing of trees, the carving of bark, the building of a shelter, the painting of clouds, the signalling of celestial objects, the radio broadcasting of positions.

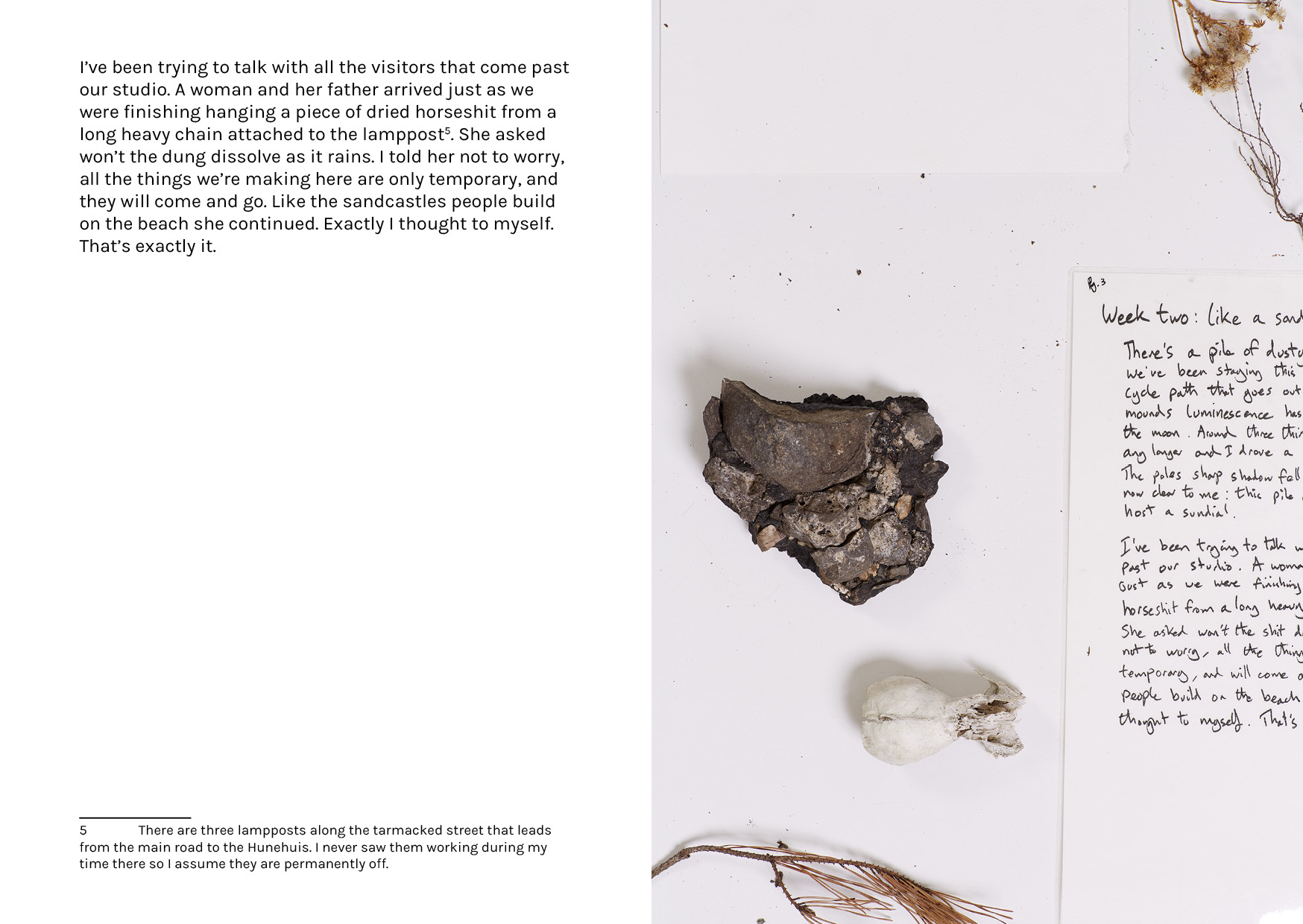

Not nature itself, but our dealings with it form the core of the work of the Scottish-Danish artist Edward Clydesdale Thomson (United Kingdom, 1982). Insofar as there is a distinction between them, of course, because in many cultures, people think and talk in terms of nature only at an advanced stage of the civilization process. Civilization in the West usually meant control of nature or, since Romanticism, the rediscovery of our (own) pure natural state. Whoever sees what he understands by nature also understands better what culture means - and that is important for many artists. When Thomson derives motifs from nature, he wants to question cultural conventions, especially those of art. Can an artist relate to his or her work as a hunter, steward or gardener relates to nature, that is to say that he allows the work to go its own way, but does keep it constant, prunes, leads, feeds and harvests? It is therefore not surprising that Thomson often refers in his work to garden architecture or to the use of decorative plant motifs in historical and contemporary bourgeois interiors.